So now that we know what antibiotics actually are, how are they used in beef farming?

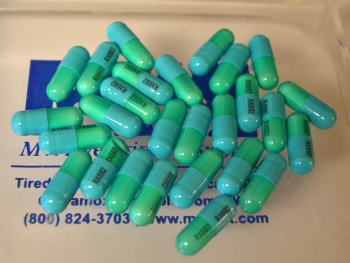

When most people think of antibiotics, they think about pills or capsules. In small animal veterinary medicine, we do often use antibiotics in the form of pills, capsules, or chewable tablets.

But in cattle things are a little different. Remember those rumen protozoa? Well, they do some funny things to antibiotics, and we can’t use these drugs (or most drugs, for that matter) in an oral form in cattle. So they have to get injections.

Sometimes we use antibiotics that are also approved for use in people, like Baytril. More often, we use antibiotics that are not approved for use in people, like Micotil and Resflor. In fact, if Micotil is accidentally given to a person it can kill them by causing a heart attack and Resflor may have side effects of bone marrow suppression in people.

Because some antibiotics that are approved for use in animals may have side effects in people, it is essential that farmers keep good records of which animals they use antibiotics in, what date the antibiotic was given, and how much antibiotic was given. The farmers then need to be aware of the withdrawal date and not sell the animal for food before that date. At the processing facility, meat can be randomly tested for antibiotic residue, or the inspecting veterinarian can request testing on the meat from an animal they have reason to think might have antibiotic residue.

If meat from an animal is found to have antibiotic residue, all the meat from that animal is condemned (discarded). The farmer who owned that animal will be subject to citations from the FDA, and may see other consequences such as jail time and not being able to sell any animals for food for people. (This can be devastating for a farmer’s business.)

So why do we use antibiotics in beef cattle in the first place? First and foremost, we use antibiotics to treat disease. Just like people, cattle can get bacterial infections that require antibiotics to treat them.

Antibiotics are also commonly used for prophylaxis, or prevention of disease. In many feedlots, cattle are brought in from many different farms in different areas of the country. Some of these cattle have been shipped in a trailer for many hours. The stress of travel and meeting lots of new cattle all at once can lower their resistance to disease and make them more susceptible to infections, especially pneumonia. When new calves enter a feedlot, most farmers will vaccinate them for the most common respiratory diseases. The problem is that vaccines take up to two weeks to be effective. And in the meantime, the cattle may be exposed to many different bacteria.

Often, when the calves get their vaccines when they arrive at the feedlot, they also get a single dose of a long-acting antibiotic. Remember the hormone implants that release hormone into the animal’s body over a period of time? Long-acting antibiotics are similar, except the antibiotics are in a liquid form and are only released for 2-14 days (depending on the medication). This single dose of antibiotic helps keep many cattle from getting sick, and needing even more medications.

Some antibiotics can also be used as feed additives. I know, I just said that we can’t use antibiotics orally in cattle because of their rumen protozoa. The medications we can use orally actuallyhave a primary effect on those protozoa, and a secondary effect on the cattle. We’ll talk about them next time.